I don’t have pets, but I do have a giant tortoise in the neighborhood.

No, not like the floods of turtles in the canals. Those ones are charming. Those ones aren’t likely to smash or devour you. Those ones didn’t do anything to receive punishment.

My neighbor is and did.

Long lived as many tortoises are, this guy has been around since before Lafcadio Hearn moved here:

…the most unpleasant customer of all this uncanny fraternity to have encountered after dark was certainly the monster tortoise of Gesshoji temple in Matsue, where the tombs of the Matsudairas are. This stone colossus is almost seventeen feet in length and lifts its head six feet from the ground. On its now broken back stands a prodigious cubic monolith about nine feet high, bearing a half-obliterated inscription. Fancy—as Izumo folks did—this mortuary incubus staggering abroad at midnight, and its hideous attempts to swim in the neighbouring lotus- pond! Well, the legend runs that its neck had to be broken in consequence of this awful misbehaviour. But really the thing looks as if it could only have been broken by an earthquake.

(Lafcadio Hearn’s “Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan,” 1894.)

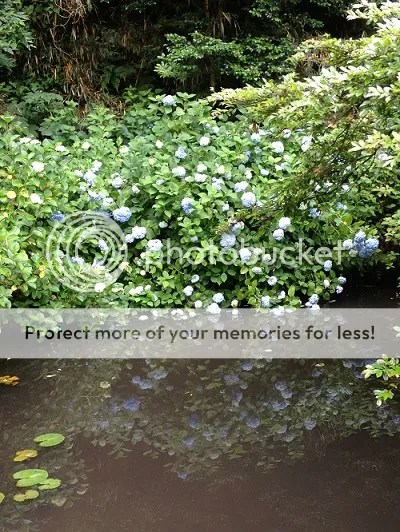

Hearn’s left a lot of common details out of this brief description. First, let’s address its home, Gesshoji Temple, frequently mentioned in this blog for its famous hydrangea and for being home to the graves of the Matsudaira fuedal lords, such as Naomasa and Harusato (aka Fumai). Each grave is decorated in different ways, including detailed carved gates in Chinese style, often reflecting the taste and hobbies of the lord buried within. It’s always a quiet place, set apart as if in its own world by the thick forest growing in and around it. Francine Prose describes the atmosphere very accurately in this Smithsonian Magazine article:

Something about the temple grounds—their eerie beauty, the damp mossy fragrance, the gently hallucinatory patterns of light and shadow as morning sun filters through the ancient, carefully tended pines—makes us start to speak in whispers and then stop speaking altogether until the only sounds are the bird cries and the swishing of the old-fashioned brooms a pair of gardeners are using to clear fallen pink petals from the gravel paths.

While wandering among the hydrangea–at their height quite soon–and hopefully not slipping on the bumpy old rock paths made slick by hundreds of years of foot traffic and by the fresh rainfall, anticipating the matcha and wagashi waiting for you back towards the entrance of the temple when you’re done with your stroll, and contemplating the peaceful world where the lords’ remains remain, you suddenly run into it.

Better that than it running into you.

I’ve heard a couple versions of the legend aside from Hearn’s relatively innocent version. Sure, the tortoise probably made a big mess of the lotus pond while splashing around in there or just wandering away from his post to geta drink. Constantly being on guard around the graves is bound to make even a stone gaurdian thirsty. But this gaurdian apparently also got bored–and entertaining himself required running amock among the neighborhood, flattening townspeople in the process. In another version of the story, he would even gobble some townspeople up.

Naturally, no one dared to attack the tortoise. What match would samurai swords be for a tortoise made of stone–a seven foot tortoise, at that? At last, a monk came and bound the tortoise to its spot by driving this sealing plaque down its back.

I haven’t heard of it moving around since, and today there is another legend that says it is good luck to rub its head, as that will bring longevity. This seems sure and safe enough during the day, but thankfully the temple usually is closed after dark–if it’s gotten hungry since it’s gotten stuck in place, then perhaps standing so close to it wouldn’t bode well for your longevity.